Donald's Blog

|

|

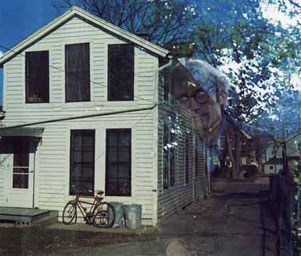

This old house was only a few blocks from the state Capitol in Madison,

Wisconsin. All the neighborhood cats lived in the basement during the

winter. The house has long since been torn down, but in 1972 there were

AR2ax speakers in the front room, and a lot of good music was heard there. |

|

|

|

In the 21st century I am just as opinionated as ever,

and I now have an outlet. I shall pontificate here about anything

that catches my fancy; I hope I will not make too great a fool

of myself. You may comment yea or nay about anything on the

site; I may quote you here, or I may not. Send brickbats etc.

to: dmclarke78@icloud.com.

|

April 1, 2012A puzzlement

My thousands of readers (ha!) will know that I adore the Times Literary Supplement, a weekly book review paper that is well over a century old, but it is true that the English think that God is an Englishman, and that they think they deserve still to be the masters of the world. This is one of the things that amuses me about them, but it means that once in a while the TLS prints something mystifying.

In the issue for March 23 there is a review of a book by Michael Khodarkovsky called Bitter Choices: Loyalty and betrayal in the Russian conquest of the North Caucasus. The reviewer Donald Rayfield writes, “The Russian conquest of the Caucasus started around 1590; it is still under way”, which is promising. I have added it to the very long list of books I would like to read if I should happen to live long enough. But along the way Rayfield writes:

Generalization is impossible: on the one hand, whole peoples, such as the Ubykh, were driven to extinction; on the other, in 1859 Tsar Alexander II treated the captive Imam Shamil with chivalry that leads us to wonder why Barack Obama could not likewise honour a trapped Bin Laden and thus, perhaps, disarm a global movement.

We know that the English are fond of the Arabs, but what can this passage possibly mean? To begin with, it is too late to honor Bin Laden, who has been dead for some time. Secondly, in what sense was he trapped? He had been cosseted for years by the Pakistani security services: either that, or they couldn’t find him, which I do not believe; in any case the only way we could get him was to invade Pakistan, illegally and however briefly. And finally, how could an American president have been expected to honor someone who was in hiding because he had enabled the murder of more than 3,000 Americans on American soil?

Who is Donald Rayfield? He is Professor of Russian and Georgian at Queen Mary, University of London, whose latest book is Stalin and His Hangmen: The tyrant and those who killed for him (2005). How would he have honoured Stalin? The only difference between the warped monsters Stalin and Bin Laden was that Stalin was actually a head of state.

April 1, 2012The WSJ magazineThe occasional and very slick WSJ magazine arrived yesterday, with the weekend edition of the paper. There is almost nothing in it except fashion photography. Predictably, the boys look either as though they forgot to pack their razors or they are not old enough to shave yet. An article about Swami Vivekananda, who brought yoga to the USA, might have been interesting, except it concentrated on his celebrity adherents (Tolstoy, Tesla, Sarah Berhhardt, J.D. Salinger) rather than what he actually taught.

I read somewhere that the magazine is very successful, which must mean that corporations are clamoring to buy advertising space. The editor-in-chief is Deborah Needleman, who used to be an editor at House & Garden, a venerable Condé Nast title which closed a couple of years ago because it concentrated on the coasts, which meant that there was no reason for most Americans to buy it.

The printing and the photography in WSJ are impressive to look at, however, which only reminds us that the color photos in the daily Wall Street Journal are so often out of register.

April 1, 2012BullyingThere seems to be a lot about bullying in the papers lately; apparently there's a film about to be released. One commentator says that despite the occasional horror story, children are safer nowadays than ever, but bullying is not about statistics. It is about individual incidents. So no matter who Trayvon Martin was, George Zimmerman followed him home from a convenience store and started trouble where there wasn't any. That is what bullies do. Nowadays the bullies are often armed; we have a lot of shooting in Allentown.

I know all about bullying.

When I was little, in Kenosha, Wisconsin, we were afraid of "big kids", because they were all too likely to be bullies. Bobby Kalick would loom out of the darkness when I was on my way home from Cub Scouts and punch me in the stomach, knocking the breath out of me so that I could not breathe, and literally thought I was going to die: I had never seen Kalick in the light, never spoken to him; he remained the archetypal bully, the original nightmare. Another kid, whose name I only knew as Mitchell, kneed me in the balls once: I did not know there was such pain in the world. But most of the bullies I knew were my own age. Kalick's brother Billy was in my class: he once saved up a huge mouth full of spit and let me have all of it in my face, so that I was gagging for hours.

Kent McCullum was a friend of mine, I thought; once we got in trouble together for throwing snowballs at a brick wall: a spinster in a classroom was irritated by the "plock" of each showball. Somewhere along the way Kent decided that he hated me, and I was afraid to leave school to try to go home; he had his confederates at each exit, and I could see him out the window, picking up my bicycle and smashing it to the ground in frustration. Kenny Knutson, a big baseball player, used to chase me home from school. I never knew why I was such a lightning rod for such people. I had friends, too, and mostly what friends were for was laughing with; what was wrong with the others?

That was at Roosevelt School. Things were worse at McKinley Junior High. There were three junior high schools; I heard Washington was even worse, but McKinley was a shithole, and Lincoln was where all my friends went. (It was geography: I lived on the wrong side of 75th Street, and my father had no strings to pull, or didn't go in for that sort of thing.) Kent McCullum was at McKinley; so was Freddie Cripps, a famous asshole. Back in my own neighborhood I loved my paper route, but every day was a trial of fear until school was over.

Finally I had had enough, and I took a weapon to school with me, on a day when I did not have gym class, and so didn't have to undress. Under my clothes I carried a crappy "hunting knife" in a cheap leather scabbord, probably a souvenir from Wisconsin Dells. All day I went up and down the dismal stairways between classes, wondering if something would happen. But nothing did, and that seemed to be the end of it: from then on everything seemed to lighten up. Had my buried rage and the limit of my frustration somehow communicated itself?

When I hear about kids killing each other or themselves, I turn the page. I've been there. Anybody who thinks it isn't a problem is a fool. In my day the schools, teachers, cops didn't care, and my parents were helpless. I don't know if things have improved or not.

Not too many years later I was working in a factory in Winthrop Harbor, Illinois, that made Silvertone TVs for Sears & Roebuck. A horrible place to work. I saw Kent McCullum there. He was one of the best-looking boys I ever knew; he could have been a model or an actor, but he had come from a rough home -- we heard that his mother borrowed condoms from him -- and the last time I saw him he was beaten down, had already lost the game of life. He didn't like the TV factory, but he had been fired from the car factory, American Motors, where the money was a lot better, because he had lied on his employment application, saying that he had never been arrested. He thought they only wanted to know about felonies, and he had been guilty only of misdemeanors. A few years ago I heard that he had long since smoked and drank himself to death.

Years later I was in the car factory, and had served an apprenticeship there. Stationed in some corner of the huge plant, if I had nothing to do in machine repair, that was good, because it meant that nothing was broken down and production was proceeding as normal. Idly walking down an aisle one day, suddenly a pudgy man loomed in front of me, and introduced himself. He was a shuffling, paunchy nebbish, so bashful he looked mostly at his shoes. It was Bobby Kalick. He had no idea how I had felt about him all my life; or maybe, at some level, he knew how little regard the world had for him. He just wanted to make some kind of human contact. I asked after Billy, who had been my classmate: "Oh, Bill's okay, been in jail a few times, but he's all right." I never saw him again.