Donald's Blog

|

|

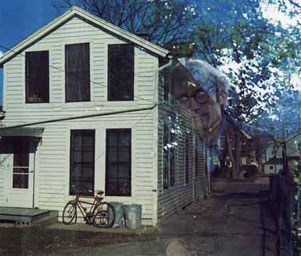

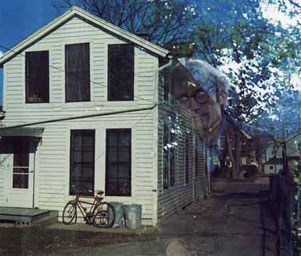

This old house was only a few blocks from the state Capitol in Madison,

Wisconsin. All the neighborhood cats lived in the basement during the

winter. The house has long since been torn down, but in 1972 there were

AR2ax speakers in the front room, and a lot of good music was heard there. |

|

|

|

In the 21st century I am just as opinionated as ever,

and I now have an outlet. I shall pontificate here about anything

that catches my fancy; I hope I will not make too great a fool

of myself. You may comment yea or nay about anything on the

site; I may quote you here, or I may not. Send brickbats etc.

to: dmclarke78@icloud.com.

|

April 27, 2012Reading the papersOne thing I managed to do almost two weeks ago during my delightful long anniversary weekend in the beautiful state of Virginia was discover a marvelous glass of beer: St. George's IPA, the nicest stuff I've ever tasted out of a bottle. (I have always wondered why beer in bottles and cans is usually too fizzy, and a knowledgeable barman recently speculated that the brewers think most people like it that way. I suppose there may be something in that; nobody ever went broke underestimating the taste of the American public.) I thought that the St. George brewery was in Hanover, Pennsylvania, but it's in Hampton, Virginia, and they don't ship outside the state. Must go back to Virginia soon.

Actually, though, I started to write about how I kept up with my newspaper reading that weekend. To begin with, before we left, on April 18, there was an article in the Morning Call about a new restaurant in New York City called Dans Le Noir, where you eat in the dark. I mean pitch darkness. You can't see the food or your companion or the waiter or a glass of water. Nothing. You have to sign a release in case you accidently hurt yourself. Some people say that when you can't see the food it tastes different. Well, I'll be darned. This restaurant has branches in London, Paris, Barcelona and St Petersburg, and there are similar experiences available in Geneva, Warsaw, and Bangkok. I do not know who would want to pay to eat in a restaurant that wishes to save that much on its electricity bill, and it makes me wonder what kind of a recession we are in that allows people to think of such weird ways to kill their time.

Then over the weekend there was an article in the New York Times called "Romney can win with Santrorum's playbook", by Ralph Reed, who is defined as a conservative strategist. The New York Times seems to have trouble finding conservative columnists who can find something to write about; maybe they should give up. This one thinks that pleas for "strengthening marriage and family" might win a presidential election this year. Skimming this nonsense, my eyes glazed over when I read that "Today Obama governs as the most left-of-center president in history". No, he doesn't. Not very long ago Obama would have been a moderate Republican.

On April 15 in the Washington Post there was an article about 19-year-old Darryl Robinson, a student at Georgetown University, who started out in a charter school with a speech impediment. He worked very hard and overcame that and became a straight-A student, although the teachers often accused him of cheating. One teacher bragged to her class that she would get paid whether or not they learned anything. Robinson made it to a very good prep school, where being accepted at a college or a university was a prerequisite for graduation, and where he began to suspect that he had not been very well educated. When he got to Georgetown it became obvious that he had been taught to pass exams, not to examine concepts or think for himself. He's working very hard, but making it at Georgetown. He keeps in touch with his prep school graduating class:

Generally, we agree that our schools did not prepare us, even though they tried. My high school was one of the best I had the choice of attending [...] but any high school administrator in Washington faces a problem similar to my professors at Georgetown: They're stuck correcting the damage done before we got there.

Robinson happens to be black, and I graduated from high school a thousand miles away and over 50 years earlier in lily-white Kenosha, but my experience doesn't sound too different from his. Why is it that a great many public-school teachers seem to be time-servers?

Then it was back to my favorite paper, the Wall Street Journal, and incidentally you get the paper of your choice for free, or even two or three if you want to help yourself, at the wonderful Williamsburg Inn in Colonial Williamsburg (the town by the way has not one but two very nice bookstores). It was such a nice weekend. And the Wall Street Journal has been a delight lately, allowing as it often does real argument and discussion.

A letter writer in Horsham Pennsylvania, Paul B. Gallagher, had his heretical opinion printed (I did not make note of the date): he pointed out that in eight years of Bill Clinton, with somewhat higher taxes, we saw nearly six times as many jobs created as during eight years of George W. Bush, with his multi-trillion-dollar giveaways to his friends, which led to the biggest economic collapse in 80 years:

We've tried giveaways to the rich, and the only people who benefited have been the top 1%. For the rest of us, they've been a dismal failure. It's time to stop selling snake oil and go back to real medicine.

I hope the letters page editor who let that through didn't get fired [joke!]. But after we got back, on April 20, there was more of the same on the opinion page: "How the Fed Favors The 1%", by Mark Spitznagel, who runs a hedge fund in California, and addressed the problem from a more specific angle. When the Fed increases the money supply, it's like feeding the sparrows by feeding the horses: most of us get to pick through the droppings. An increase in the money supply is essentially inflationary, good for those who get the money first (the bankers), but those who partake last actually suffer: you could make an analogy with the lack or nourishment in horse apples. When the Fed expands the money supply

it directs capital transfers to the largest banks (whether by overpaying them for their financial assets or by lending to them on the cheap), minimizes their borrowing costs, and lowers their reserve requirements. All of these actions result in immediate handouts to the financial elite first, with the hope that they will subsequently unleash this fresh capital onto the unsuspecting markets, raising demand and prices whenever they do.

In other words causing a spree of investment, which often goes wrong, as in the dot-com bust of 2000-02, and the more recent frenzy of swapping bundles of toxic mortgages; and of course the richest people get to keep their gains when the horses stop pooping for the rest of us.

Spitznagel doesn't really propose an alternative way of increasing the money supply, but he does make a point.

Pitting economic classes against each other is a divisive tactic that benefits no one. Yet if there is any upside, it is perhaps a closer examination of the true causes of the problem. Before we start down the path of arguing about the merits of redistributing wealth to benefit the many, who not first stop redistributing it to the most privileged?

And on the same page on the same day, Alan S. Blinder, a professor of economics and public affairs at Princeton University and a former vice chairman of the Fed, wrote about the Supreme Court and Obamacare. The "mandate" requiring that everyone buy health insurance is related to the reforms in the insurance industry. In selling any kind of insurance, the industry spends a lot of money trying to screen out bad risks, for example in health insurance by disallowing pre-existing conditions. If everyone is required to have health insurance, the industry gets a lot more customers and a lot less adverse selection, and can save all the money it now spends on screening.

So what happens if the justices void the mandate but leave the insurance reforms in place? The answer is: we get incoherence. Which, of course, is why you don't want judges making economic policy.

Blinder concludes: "If we are going to have political decision making, at least elected politicians should do the deciding. Come to think of it, they already have." Congress passed Obamacare. And there is no doubt that health insurance is interstate commerce, which Congress is allowed to regulate.

This of course was too much for the Journal's readers. Four long letters in today's paper unanimously excoriate Blinder. Basically of course they all want the freedom to choose, as in the old saying about the rich and the poor having the equal right to get wet when it rains. To quote one at random:

The solution is not to mandate away individual choice. The solution to the cost problem is to establish a health-insurance program that allows consumer choice and competition to make costs affordable.

Ah, let the market do its work, so that some people won't be able to buy any health insurance because they can't afford it no matter how much it costs, and where young and healthy people won't buy it because they think they don't need it, which will keep the cost up. Let's not have any reform at all, in other words.

The best solution would be to get the insurance companies out of it altogether, but that won't occur to the sort of people who write to the Journal, and won't happen in my lifetime. But at least there's some discussion going on.